Priest of Darkness is an attempt to bring the historical reality to the (historical) present.

Typical of Yamanaka’s work, Priest of Darkness revolves around multiple characters within a tight “community” and a lost object, a knife that one of the protagonists, Hirotaro, steals from a samurai and then sells onward. He is a trouble-making brother of a young stall keeper Onami (16-year-old Setsuko Hara in one of her earliest performances) who finds herself in trouble as she tries to level with her brother and solve his debts. The absence of a straightforward plot is notable in the way Yamanaka navigates freely between multiple characters. In addition to the siblings, they include limping samurai Kaneko, the titular “priest of darkness” Soshun Kochiyama, and his wife who all end up assisting Hirotaro and Onami in trouble. Some of the crucial events in the film happen completely outside of the frame and often we run into previously unheard characters like the henchmen of a local mob boss who try to recover debts from Hirotaro.

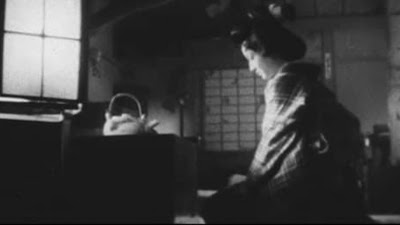

More essential than the plot of the film is its setting, an anonymous, lower-class neighborhood filled with little houses and narrow alleys that Yamanaka shoots with attention to detail by utilizing deep

staging. At the beginning of the film, the background is teeming with people on the move, enjoying the evening’s festive atmosphere. Even as the film progresses, the depth of the field is an important playground for Yamanaka and serves the naturalistic purposes he presents. The focus on spatial relations emphasizes the characters as part of their surrounding. The way they quietly

hide in the background and find comfort from the numerous doors and walls of their surroundings heightens the sense of being unable to escape from the spot they are in. To strengthen their alienation, Yamanaka often positions the brother and the sister to the background of the frame with their backs or another side of the face against the events that are taking place in the foreground.

Therefore one gets the feeling that the siblings are only partly present, hiding their true emotions from each other and the possible witnesses (there’s only one scene in which the sister reveals her true emotions to the brother, and a child spying on the event). The way people move in their surroundings becomes a bigger focus for the filmmaker than the drama itself. Actually, their movement is the drama. In the end, Yamanaka is more of a behaviorist than a psychoanalyst.

Whereas Yamanaka’s earliest surviving film, Sazen Tange and the Pot Worth Million Ryo (1935) is more humoristic and its characters borderline parody (notably the title “hero” who, in Freda Freiberg’s words, “is more interested in wine and women than action”), anxiety and sobriety define heavily the relationships of Priest of Darkness. The film has its vivid comedic moments, like the bidding contest for the stolen knife between two samurai friends who also accidentally sell it back

to its original owner who thinks it’s a fake, but the gulf in relationships between men and women makes the disconnection resonate profoundly. Women sacrifice for men yet they can’t expect the same from them. Men are intensely involved in their freewheeling endeavors with zero responsibility towards their fellow human beings. Consequently, Priest of Darkness turns traditional gender roles upside-down and depicts active women (especially Hara as Onami looking out for her

brother) and passive men.

Like Freiberg has noted, Yamanaka’s later films presented a move from light to a darker tone. In the atmosphere of growing Japanese militarism, he was also deeply influenced by still vital leftist cultural circles. The director’s fascination with theater isn’t only visible in his preference of long shot and focus on blocking but in the collaboration with the modernist and Marxist theater group Zenshinsa whose participation explains some of the detail (Zenshinsa was notable for its focus on historical accuracy) and the seriousness of the film. The criticism of social inequalities like poverty, youth’s aimlessness, hierarchism, and oppression of women separate the film from Sazen Tange’s attempts to comment on the conventions of jidaigeki (“period piece”) and move towards more socially engaging filmmaking.

Compared to Yamanaka’s two other surviving films, Priest of Darkness is considered to be his lesser effort. The film does feel like a rough transition work between a meticulously realized critical parody of Sazen Tange, and Humanity and Paper Balloons’ concerns for the balance between full-blown naturalism and tender poetry, but it does manage to stand on its own as more than just a historical curiosity. The film’s strength lies in Yamanaka’s subtle sensibilities in utilizing the relationship between what’s in the frame and what is not (also when something is in the frame and when it’s not). Priest of Darkness is an attempt to bring the historical reality to the (historical) present. The film is a synthesis of then and now in which the emotional deficiencies of its characters are laid open, and their connections to material conditions are made tangible with detailed and carefully crafted mise-en-scène. Even if Yamanaka never lets the viewers spend enough time with the film’s characters to understand their actions fully, he makes sure that every shot matters and reveals to us their human weaknesses and strengths. What the film loses in a shabby script, it wins back with masterful direction.

Comments

Post a Comment